The high-luminosity upgrade of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is set for a critical year in 2026. The project, called HL-LHC, aims to increase the integrated luminosity of CERN’s famous collider by a factor of 10 beyond the LHC’s design value.

This new era of the collider is set to begin in mid-2030, following a long shutdown (LS3) of the LHC that begins in July 2026. This shutdown will allow many of the major HL-LHC installations to be carried out.

Ahead of the shutdown, the HL-LHC team will perform a crucial high-intensity beam test that will provide insights into how the current infrastructure will hold up against the higher intensity. In this article Sofia Kostoglou, Nicolas Mounet, Stefano Redaelli and Rogelio Tomás García explain the reasons for the high-intensity beam test, and the preparatory work that will be carried out ahead of the test.

The challenges of reaching high-luminosity stored beam energies

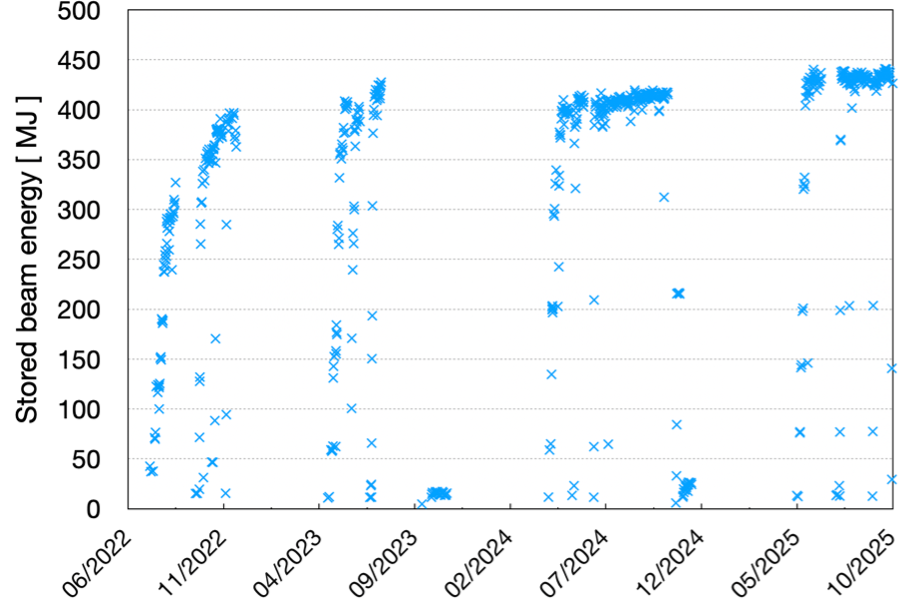

The performance of the LHC during Run 3 (2022–2026) has far surpassed its original design goals, routinely reaching stored beam energies of more than 450 MJ in proton-beam operation (see figure 1 for achieved values throughout Run 3). This excellent performance is, however, still short of what is planned for the upcoming HL-LHC upgrade, which requires a further increase in both bunch current and the number of bunches to reach the ambitious target of 700 MJ. Achieving these unprecedented beam parameters relies on pushing the bunch current to the target value of 2.3 × 10¹¹ protons per bunch at injection into the LHC.

Reaching this goal in a superconducting collider such as the LHC is extremely challenging. Many beam dynamics aspects related to high beam currents must be mastered to ensure the design performance: beam instabilities, beam-beam interactions, beam collimation and machine protection issues, and electron cloud effects. Furthermore, the HL-LHC baseline parameters rely on complementary projects such as general LHC consolidation, high efficiency klystrons, and beam screen treatment with amorphous carbon, planned for implementation during LS3.

In addition, it is essential to rule out any limitations in the existing LHC equipment that could prevent reaching the target beam intensity. This is a well-known concern for accelerators such as the LHC. For example, in 2017, due to air being trapped in the 16L2 area, the LHC had to operate with a reduced number of bunches in the “8b4e” configuration (a particular way of spacing the proton bunches in a train: eight proton bunches are injected spaced 25 ns apart followed by four empty slots – i.e. 100 ns of space. Usually, the nominal beam is made of trains of 72 bunches simply spaced 25 ns apart with no empty slots.

In 2023, the LHC used a mixture of 8b4e and standard 25 ns beams to optimise luminosity production with acceptable heat load in the beam screens. In 2025, the bunch charge in Beam 1 could not be increased above 1.6 × 10¹¹ protons due to impedance heating of a vacuum module. In the worst case, such heating could cause damage to components – such as radiofrequency fingers losing their mechanical properties – resulting in deformation and potential obstruction of the beam-stay-clear aperture.

Depending on the severity of these non-conformities, operations might either continue with temporary intensity limitations until subsequent end-of-year stops or require immediate interventions. Either scenario would be detrimental for the HL-LHC, where beam intensity and machine availability are essential for achieving the integrated luminosity goals from the start of Run 4.

The high-intensity beam tests

To minimise the risk of encountering such limitations during HL-LHC operation, a dedicated high-intensity beam test is planned for the end of the 2026 run, with preparatory experimental work having already taken place in 2025. During this test, HL-LHC-type beams – already available from the injector complex – will be injected and accelerated in the LHC to identify any potential limitations at an early stage.

Several options are being considered to mitigate the existing limitations while still addressing the core objective of identifying beam-induced heating effects on machine components. The most promising scenario for the nominal beam scheme is to fill the machine at an intermediate energy of 3 TeV, where electron cloud and intra-beam scattering remain tolerable, while the beam-induced heating is comparable to that expected at the HL-LHC. The 8b4e beam can be safely taken to top energy and allows the establishment of collisions for additional critical tests, including potentially some detector components like the LHCb velo and the Roman pots.

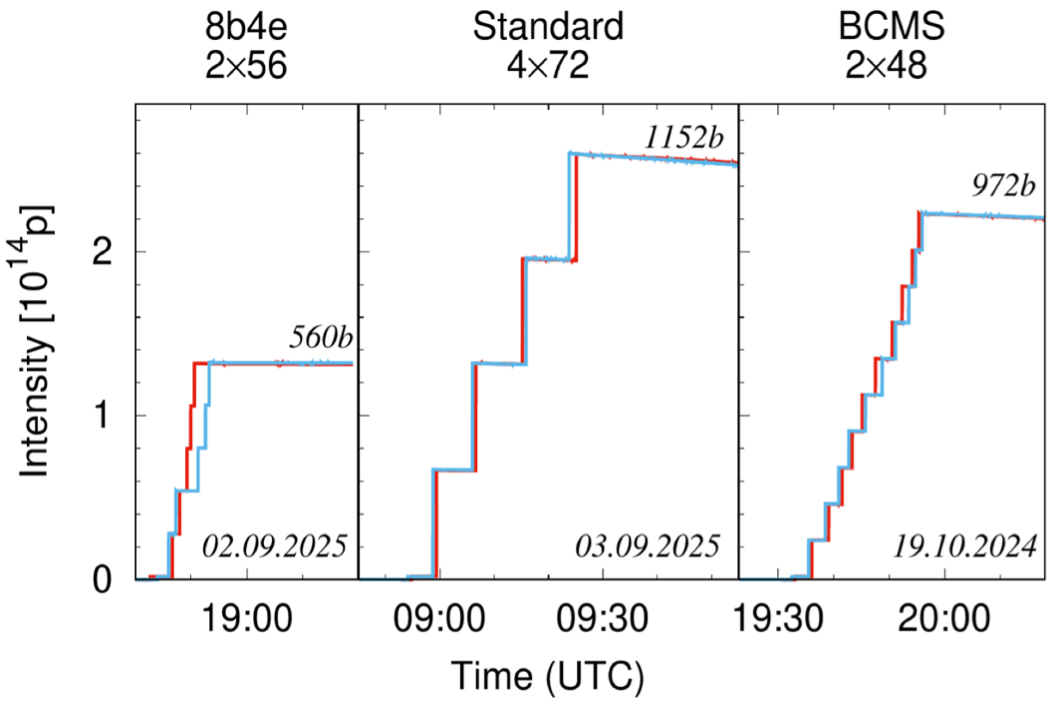

Preparations for this crucial high-intensity test in 2026 are already well underway. Together with BCMS beams (a type of beam different to the nominal beam, but still with 25 ns spacing) that are the operational beams in Run 3, three different upgraded (LIU) beam types have already been injected into the LHC (see figure 2), and collisions were established for the first time with a few trains of 8b4e LIU beams reaching the HL-LHC nominal event pile-up. Developments for a 3 TeV energy ramp are also well advanced, building on preparatory work carried out for other Machine Development (MD) studies: the LHC has already successfully ramped up to this energy and stored 1,200 bunches of 1.4 × 10¹¹ protons per bunch, aiming at 2.3× 10¹¹ protons per bunch in dedicated 2026 MD studies. The detailed plans for the 2026 test were further discussed during the LHC MD Days, that took place from 9 to 12 December, 2025.