One proposal put forward in CERN’s search for its next particle accelerator to succeed the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), due to be retired in the 2040s, is the Muon Collider.

The idea for this accelerator dates back to the 1960s, and today a large community of scientists and engineers, from Europe, the US and beyond, are involved in developing the technologies that would take the project forwards.

The Muon Collider idea was submitted to the European Strategy for Particle Physics update (ESPPU) to be considered as CERN’s flagship accelerator in the post-LHC era and to provide a long-term path for the future.

In this interview, CERN accelerator physicist and member of the International Muon Collider Collaboration Taylor explains the background of the accelerator, its novel approach to discovering new physics, and how it could advance technologies to benefit society and industry.

You can read similar interviews with representatives of the Future Circular Collider (FCC) here, and the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) here, two other proposed future accelerators. You can also read an interview with a group that recently published a comparison study of six of the proposed future accelerators here.

*This interview was carried out before the electron–positron Future Circular Collider (FCC-ee) was announced, on 12 December, as the preferred option of the European Strategy for Particle Physics (ESPP) to be CERN's next flagship collider. Read more about the announcement here.

What is the muon collider project?

The muon collider is a unique, high-energy collider concept that produces, cools, accelerates and collides two muon beams of opposite charge. This paradigm-shifting collider would be the first with both the high-energy reach of a hadron collider, and high precision due to the fundamental nature of the muon.

Proposed in the late 1960s, the muon collider idea inspired several design studies and experiments including the Neutrino Factory and Muon Collider Collaboration (NFMCC), the Muon Accelerator Programme (MAP), and the Muon Ionisation Cooling Experiment (MICE), and a muon target experiment (MERIT). These efforts delivered a staged 3 TeV design, and crucially the first demonstration of single-muon ionisation cooling.

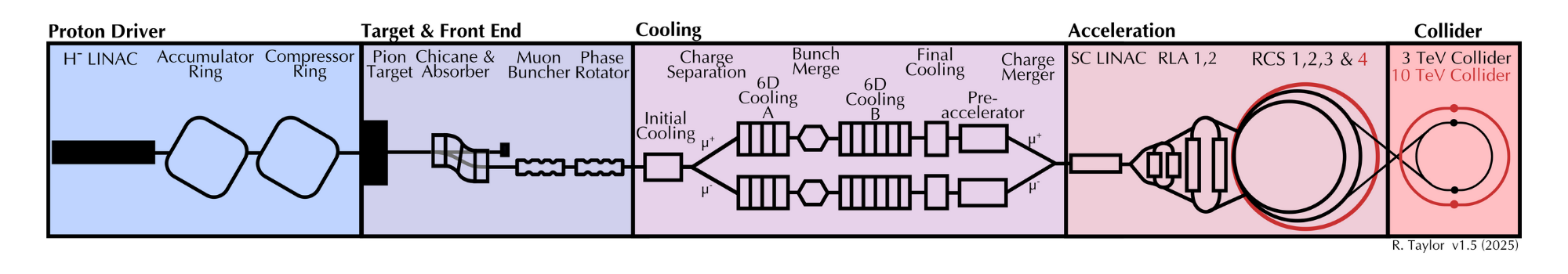

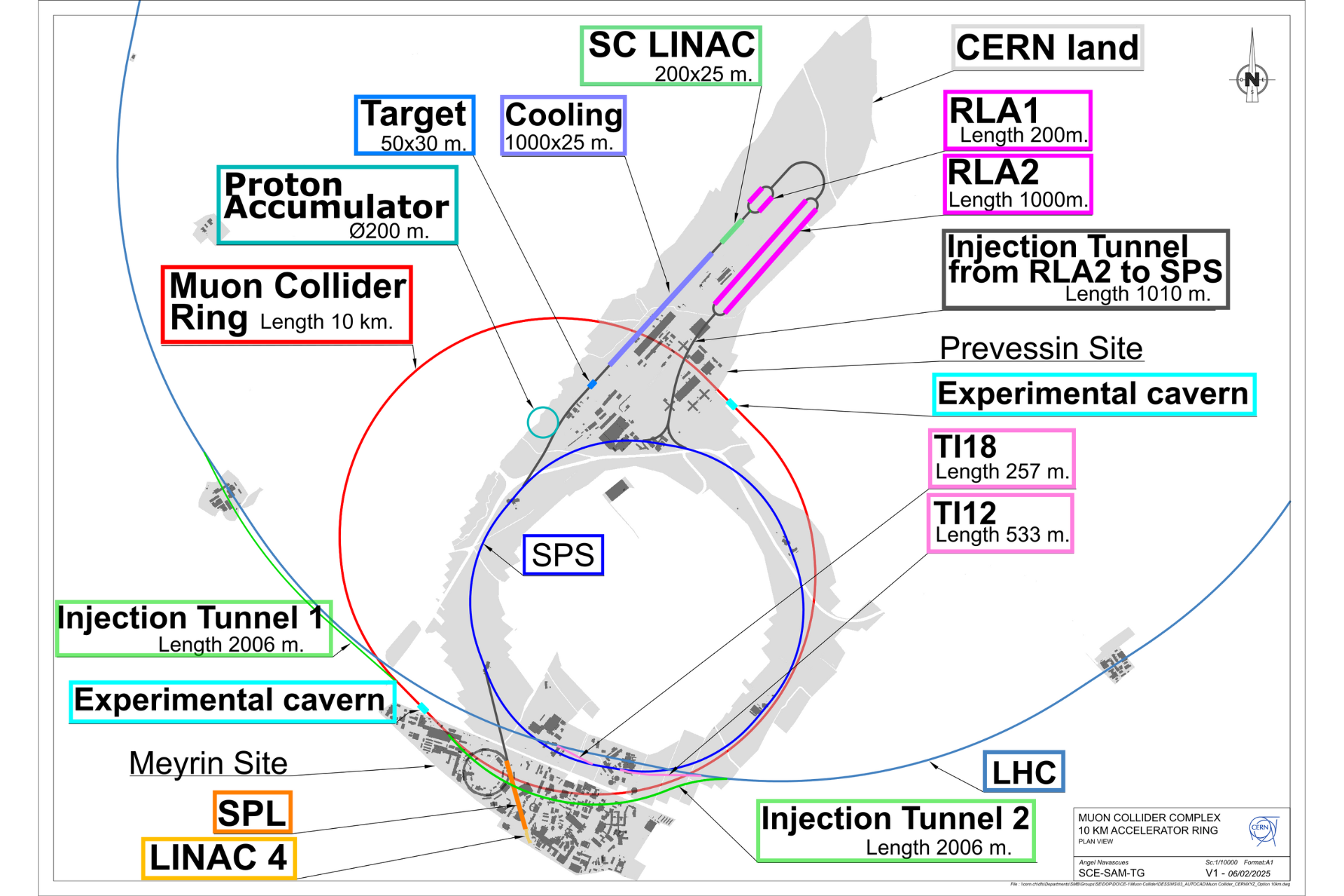

Today, the International Muon Collider Collaboration (IMCC) and the EU-funded MuCol project have submitted a 10 TeV muon collider facility design to the European Strategy for Particle Physics Update (ESPPU). The design uses a high power proton source on a graphite target to produce pions which eventually decay to yield 45 trillion muons per beam. A line of light-element absorbers would be used to reduce or ‘cool’ the beam size in six dimensions, within strong solenoid fields. Stages of LINACS and four Rapid Cycling Synchrotrons (RCS) successively accelerate the beams to 62.5 GeV (which is half of the Higgs mass), 1.5 TeV and 5 TeV. A dedicated 10 km tunnel would bring the beams to collision inside two underground detectors, known as MUSIC and MAIA.

What is the current status of the project?

IMCC and MuCol have made significant progress since their launch. A comprehensive design report has been submitted to the 2025-2026 European Strategy process, detailing the physics programme, detector design, accelerator design, site-based implementation and the proposed R&D programme required to deliver the muon collider. Three significant achievements stand out.

- Critical parts of the accelerator complex have been designed, including the muon production and cooling system, pulsed accelerator and collider ring, showing the possibility to deliver extremely high energy and luminosity. Important progress has been made on the technologies used, which now calls for an experimental programme.

- Noise in the detector, which would arise from muon decay electrons, has been characterised and shown to be manageable compared to other proposed energy-frontier machines. Detector and shielding concepts have been established which can deliver the excellent physics programme.

- A consolidated parameter set and civil engineering layout for a muon collider at CERN has been developed, almost entirely reusing the existing CERN complex.

Today, the muon collider design is sufficiently advanced that model and prototype construction of the technologies, such as magnets, cryogenics and cooling cells is now crucial to continue to develop our understanding of each of the key systems.

What would the muon collider allow us to explore in terms of physics?

Muons are heavy fundamental particles with a lifetime of 2.2 microseconds. Whilst this lifetime is short, energetic muons experience a lengthened lifetime due to relativistic effects, giving time to accelerate them to multi-TeV scales.

Like other colliders, a muon collider can yield deep insight into the nature of matter. Unlike protons, muons are fundamental particles so they can carry all of their energy to collision. This means a 10 TeV muon-antimuon collision could deliver physics insights comparable to those of a 100 TeV proton-proton collision. Unlike electrons, muons do not emit x-rays as they are accelerated or bent, so it is possible to accelerate muons to high energy using a ring.

The muon collider’s most distinctive strength appears at high energies, where it operates as a powerful vector boson fusion factory. At multi-TeV scales the muon beam contains effective gauge bosons that behave almost like massless radiated particles. These gauge bosons act as partons inside the muon and probe the quantum structure of interactions in a way that is fundamentally different from any classical picture of a composite state. This creates access to a regime where scattering processes could reveal the connections between the electroweak and Higgs sectors.

It would also give access to test scenarios of physics beyond the standard model (BSM), including dark matter, naturalness, and the nature of the electroweak phase transition in the early universe.

Neutrinos produced in the decay of muon bunches provide a bright and well-characterised beam of collider neutrinos for a forward detector. The neutrino physics programme at a muon collider provides a high-energy complement to current and future long-baseline neutrino experiments.

What are the main technical challenges?

Building such a facility would be a scientific and engineering revolution. Rapid cooling and acceleration is required owing to the large initial beam size and the short lifetime of the muon.

In particular, it is necessary to study the integration of a compact ionisation cooling cell combining solenoids, absorbers, dipoles and radiofrequency (RF) cavities within the same cryomodule and demonstrate satisfactory beam transport through the system. The ionisation cooling system and other parts of the facility benefits from development of advanced magnets, for example using high-temperature superconductors. In the acceleration system fast pulsed magnets must be developed for the rapid-cycling synchrotrons requiring highly efficient power supplies, converters and magnets.

When the muon decays, it produces an electron and two neutrinos. Decay electrons cause backgrounds inside the detectors, requiring tungsten shielding. High-energy neutrinos propagate over long distances, so their distribution must be studied when assessing the collider geometry, siting and safe operating energies.

Why does the scientific community need the muon collider — and why now?

The muon collider changes the way we approach high-energy physics. Instead of choosing between a discovery machine to search for new high-energy phenomena, or a precision machine to generate and probe the properties of known particles, the muon collider chooses both. This ambition depends on advances in accelerator technologies that would have important societal benefits beyond the particle physics community.

The physics processes of electron-electron and parton-parton collisions are well studied. In a high-energy muon collider, vector boson collisions dominate, which has not been tested experimentally. This creates a unique opportunity to study electroweak interactions, and the deeper role of the Higgs boson in higher-order standard model effects.

The muon collider presents a pathway towards a more sustainable future for particle physics, opening up a new landscape for exploration. It pushes the limits of human technology in all aspects: the magnets, RF cavities, the timing, the target. And the short lifetime of the muon forces the design to optimise for compactness and efficiency. Any technology breakthrough in any accelerator field will increase the feasibility of this system.

Who is behind the project?

The IMCC has more than 450 collaborators and over 61 member institutions, and is still growing. IMCC is hosted at CERN and includes major contributions from European, US and Asian partners, including laboratories and universities. The development of bright muon beams were identified as a High Priority Initiative by the 2020 European Strategy for Particle Physics Update and considered by the P5 panel as being a “Muon Shot” opportunity for the US particle physics community to host an energy frontier collider.

The innovative nature of the muon collider in its accelerator, detector and magnet technologies has attracted a vibrant community of early-career researchers, many of them contribute directly to key systems across the accelerator and detector complex.

This enthusiasm results in a rich training ground for future generations, which is essential for any next-generation collider proposal.

This engagement also reflects the findings of the ESPPU early career input, where 804 respondents identified innovation as their highest priority for the next collider facility, even above the physics baseline. Recommendations 4.4 and 4.7 underline this preference clearly.

What new technologies could emerge from the muon collider that could benefit society?

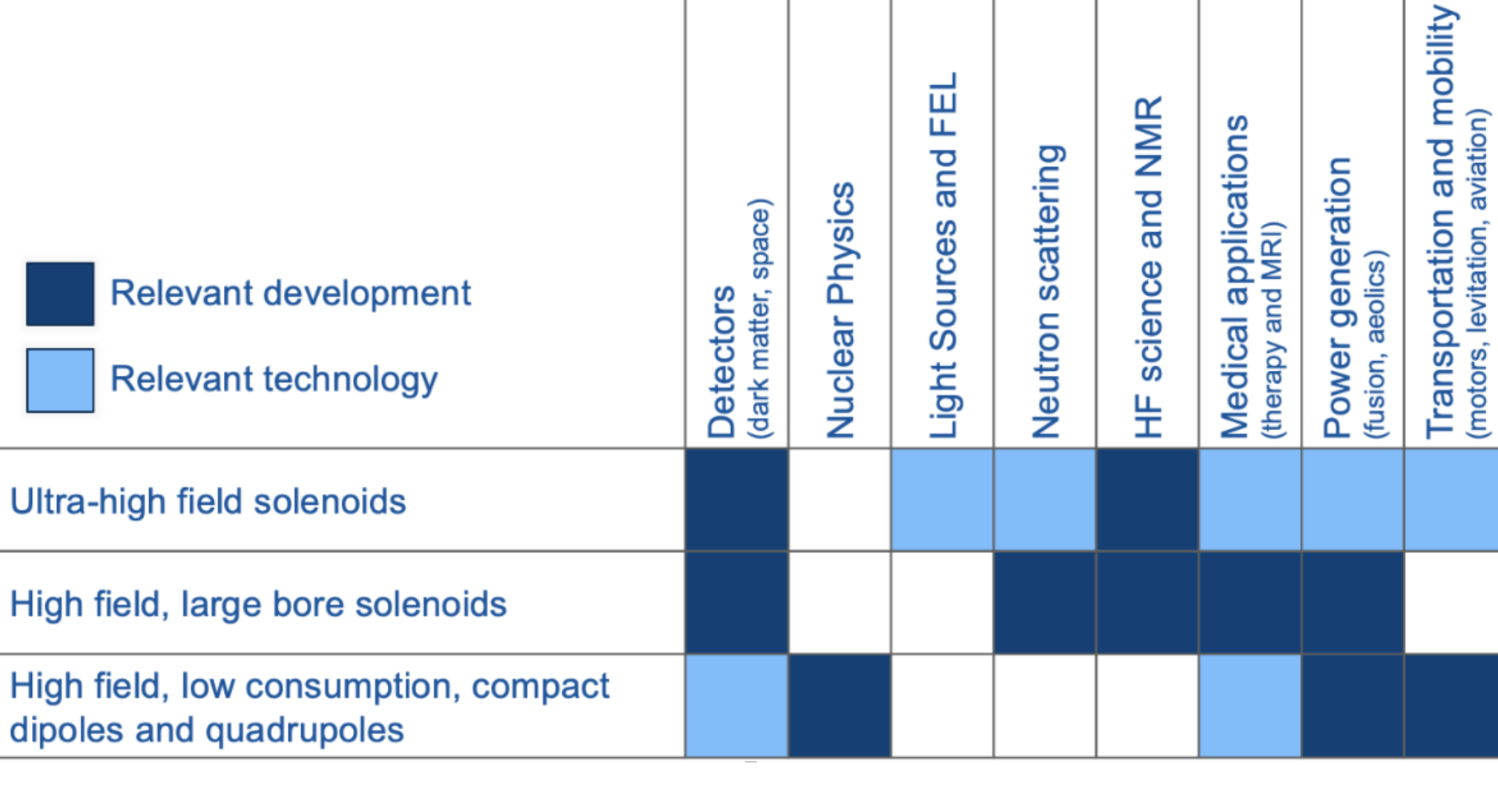

The technology developed for the muon collider will be directly applicable in broader society. Each subsystem brings different benefits to society.

Advancements in compact, high-intensity muon sources has the potential to create portable muon tomography systems for long-range imaging of large structures.

The target will be placed in a high-temperature superconducting solenoid with high-field and larger aperture, a technology that is critical for future fusion reactors. Collaboration with industrial partners has started.

High-field solenoids for the six-dimensional cooling would advance research MRI by improving resolution.

Having high-temperature superconductors would simplify cryogenics for reduced healthcare expenses.

Ultra-high field solenoids used in the final cooling may support studies of materials under extreme conditions, which would explore the future of novel superconductors, nanostructures for storage in next generation electronics, and more efficient batteries. They also enhance the diagnostic power of NMR in chemistry and biology.

The fast ramping dipole magnets require fast and efficient power converters, which aligns with industrial interest in pulsed power systems for sustainable energy grids.

High-field collider magnets contribute to compact gantries for particle therapy delivery systems. Their complex three-dimensional polar windings offer benefits for generators and motors in applications such as wind energy.