A recent CERN-organised event on the potential of building a muon particle accelerator demonstrated the enthusiasm that the topic holds for early career researchers. There are several ideas for future particle accelerators in the pipeline around the globe, but the possibility that a muon collider could feasibly be built in the life-time of young researchers and would open up the door for possible new physics discoveries is proving to be an attractive premise for many.

The interest in a muon collider was evident during the CERN online event Early Career Researchers & Muon Colliders, which took place on 28 August and attracted 188 participants from around the world. It was organised by six early career researchers (ECRs) from CERN and Fermilab on behalf of the International Muon Collider Collaboration (IMCC) for three reasons: to demonstrate the enthusiasm that ECRs have for muon colliders; to showcase contributions of current ECRs; and to provide an opportunity for ECRs to share their questions and thoughts to the IMCC coordinators.

The event covered six overview talks on the collider’s key subsystems from the IMCC ECRs working on them, featured seven research presentations by ECRs, and a one-hour Q&A with three IMCC experts. The first and most popular talk was on the physics and discovery potential of a muon collider from Cari Cesarotti (MIT). The muon collider promises a Higgs precision program complimentary to that of a Higgs factory as well as explorations to new energy regimes where new physics might be hiding.

The successive talks highlighted the challenges and intrigue of designing the muon complex for each subsystem, from the early career individuals who are driving these designs.

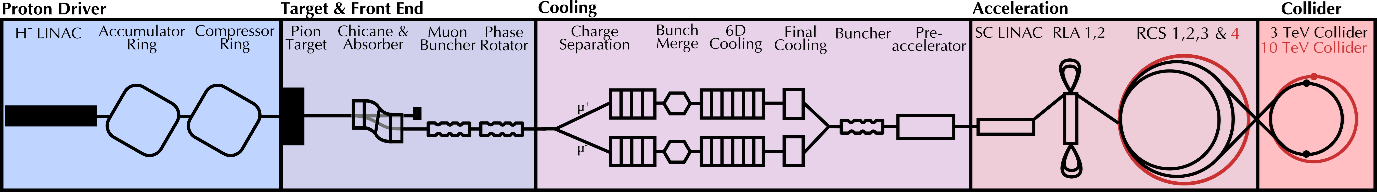

Muons are first produced from a high energy proton beam hitting a target, the process of which was described by one speaker Daniele Calzolari from CERN. The resulting muons have a wide distribution, and need to be cooled, and Calzolari explained how to produce muons from proton beams on a target.

Details of how to cool the resulting muon beam were shown by Bernd Stechauner (CERN). The cooled muons have a low energy, so need to be accelerated to 1.5 TeV or 5 TeV; David Amorim (CERN) described why a unique accelerating chain was required to get to these energies.

Then finally the muons have a dedicated collider ring for 3 or 10 TeV centre-of-mass collisions, and Marion Vanwelde (CERN) summarised the challenges of colliding these beams to get the required luminosities for experiments.

Each of these systems require their own advanced magnet designs, and Giuseppe Scarantino from Italy’s National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) gave an overview of the magnet technology challenges required for each of these subsystems. Finally, Kiley Kennedy from Princeton University in the US spoke about how to design a detector suited to a muon collider.

One of the key takeaways from the event was that while there are challenges that must be overcome to build a muon collider, there are “no showstoppers”, meaning no technical problem that could not be solved given enough research and innovation.

Only a quarter of the attendees currently work on muon colliders, demonstrating the popularity of the topic to an outside audience curious to learn more. Of the remaining three-quarters, all of them expressed their interest in working on the muon collider in the future.

During the Q&A, IMCC coordinators Donatella Lucchesi (INFN & Universty of Padova), Daniel Schulte (CERN) and Luca Bottura (CERN) concluded by describing the working environment as “lots of fun”, with researchers having “plenty of freedom” and the atmosphere being “very dynamic”.

This sentiment was reflected in the wide mix of participant’s interests, which was equally distributed between experimental particle physics and accelerator physics, closely followed by detector physics, data science, engineering, magnet design and theoretical physics.

The International Muon Collider Collaboration was true to its name with attendees from 38 countries, the most coming from Italy, the US, India, the UK and Türkiye.

CERN played a leading role in driving this enthusiasm, with five of the six organisers from CERN, and with 28 of the 188 participants from CERN – the most of any institute, followed by INFN with 13 participants.

Many people ask what defines an early-career researcher; within this event there were 13% undergraduates, 20% masters students, 30% PhD students, 25% post-docs, and 8% staff. Gender representation was high as well, with women making up 40% of the audience, and 50% of the speakers and organisers.

The creative energy from the event was strong, with many new slogans emerging from the slides, including YMCA (Yes, Muon Collider Antics!), “Buy one get one free” (referring to two physics channel benefits at the collision: direct annihilation of µ+ µ-, and also vector-boson fusion reactions) and even a new mischievous mascot, Mio the Calico

One participant summarised the efforts with a quote from Economist, E.F. Schumacher: “Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius — and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction.

All talks referenced in this article can be found on the corresponding Indico page: indico.cern.ch/e/muoncollider_ecr